Introduction

Gaining experience in the area of

jazz drumming can seem like a daunting task. Listening to advanced players,

and perusing books on jazz coordination, may cause the inexperienced player

to think the process is far too complex. This does not have to be the

case. I believe we can identify some simple concepts and principles, and

by developing them go a long way toward becoming proficient jazz players.

That's what this article is about: explaining some of the basic concepts

of jazz drumming and demonstrating simple ways to get started. 'Simple'

will be the key word here. There are enough books and materials dealing

with the complexities of jazz. This article takes a different approach

and looks at some characteristics of jazz drumming that you can develop quickly

and apply. In that regard, this article is a jumpstart

in jazz drumming. It is not meant to be a definitive explanation of every

aspect of jazz drumming, rather it is intended to explain the most essential

principles. I have tried to focus on those elements of jazz drumming that

will provide the biggest payback and get you started the quickest. Included

are suggestions and exercises that will help you develop the basic skills necessary

to play good sounding jazz drums. I have also provided some Do's and

Don'ts that may help you avoid common pitfalls. I hope that by understanding

and applying the concepts outlined in this article your jazz drumming will become

more mature, authentic, and stylistically correct.

Part 1 - The fundamentals

The aural tradition

An important point to keep in mind

when learning jazz is that the process is an aural one. This means that

we should focus on sound rather than written examples. Many people try to learn

jazz drumming by buying a book and working through the exercises. I do

not feel this is the best approach. Instead we

should focus on jazz as a language and learn its

vocabulary. One of the best ways to learn any language is by immersion.

Immersing yourself in the language of jazz will go a long way toward helping

you build a stylistically correct vocabulary. The importance of listening

to, and absorbing as much jazz as possible, can not be overemphasized.

This is the single most important key to your success. If you are

going to communicate intelligently in the jazz idiom you must know the vocabulary.

Sound should precede

notation

When learning jazz we are actually

trying to develop our ears. We want to involve ourselves in the jazz tradition

and learn its language. After we have a good grasp of the language of

jazz we can begin studying its notation. Think of notation as a way to

communicate what others have played. It should not be our starting point.

A good analogy is the way in which young children learn to speak. Children

learn to speak by listening to those around them. They imitate the sounds they

hear and learn the language in a natural way. Most children learn to speak several

years before they start to read. Learning jazz is a similar process: sound should

precede notation. If you want to learn how to play jazz you should listen to

skilled jazz players and imitate their playing. Don't worry about books,

but focus on sound. I am not advocating that we totally disregard reading or

notation. I am just suggesting that we start by listening to, and imitating

good jazz drummers. Too many people get hung up on studying jazz books

at too early a stage. There will be time for books later. After

you have spent a reasonable amount of time assimilating the jazz language it

will be much easier to grasp the written notation.

A comment about the notated

examples

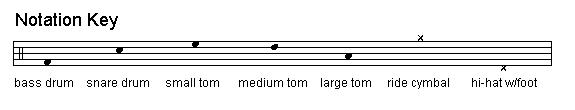

In view

of the fact that notation is secondary to sound,

you may wonder why there are notated examples in this article. The answer

is convenience. In a written article notation is the easiest way to communicate

and clarify a musical idea. That being said, the notation is really not

that important. The important thing is to understand the concepts and

apply them in your playing. All of the notated examples are very simple

and can be quickly grasped. Once you understand a concept, forget about

the notation and concentrate on its musical application.

Now that we have covered some background let's get into the principles that will allow you to jumpstart your jazz drumming.

The

foundation: the ride cymbal

The foundation of modern jazz

drumming is the ride cymbal. It will be our starting point. The

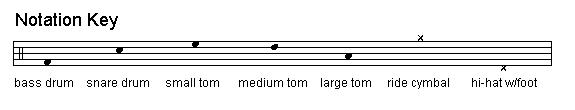

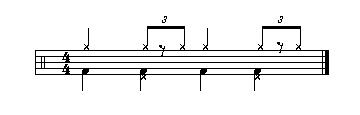

essence of a good jazz cymbal rhythm is the quarter-note pulse. Try playing

straight quarter-notes on your ride cymbal as in Example 1. The

normal playing area will be approximately half-way between the edge of the cymbal

and the edge of the bell. This playing area will give a nice blend

between definition and wash. Closer to the bell equals more

definition. Closer to the edge equals more wash. At this point

it might be good to mention that the cymbals typically used in jazz playing

are thinner than those used in rock or pop music. In jazz, the ride cymbal

provides a cushion or drone effect. A heavy cymbal with a lot of ping

will negate this effect. It will not have the necessary sustain to provide

a cushion for the soloist. Choice of sticks is also important. Select a stick

that is not too heavy or with too large a bead.

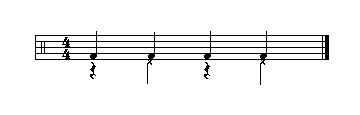

Ex. 1

The quarter-note ride cymbal rhythm is our foundation. Find some slow to medium tempo jazz recordings (a few are suggested at the end of this article) and practice your quarter-note ride cymbal pattern by playing along with them. Focus on getting a good sound out of the cymbal. The quarter-note pulse should be straight-ahead. There should be no uneveness or accents from beat to beat. Listen to the music and try to fit your quarter-note cymbal rhythm into what the other musicians are playing. The goal is to swing. This is largely conveyed by an attitude and a conviction in your playing. Don't overlook the importance of a good, solid quarter-note cymbal rhythm. You will build on it for the rest of your jazz drumming vocabulary. Beyond it's usefulness as a learning device, a straight quarter-note cymbal rhythm is a practical and useable pattern in it's own right. Many players have used a simple quarter-note ride cymbal to great effect.

The hi-hat

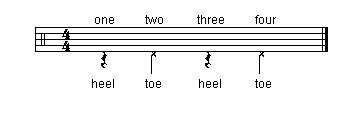

Now let's add the hi-hat. In

straight-ahead jazz drumming the hi-hat is typically played on counts 'two'

and 'four' of the measure. There are at least three techniques

that may be employed: 1) the rocking motion 2) bouncing the whole leg 3) flat-footed.

While each technique is important and has its uses, the one I will describe

is the rocking motion. This is a good fundamental hi-hat technique and

worth mastering. The technique is executed as follows: On count

'one' the heel comes down on the heel-plate, while at the same time the

ball of the foot is raised off the pedal. On count 'two' the ball

of the foot comes down on the footboard and the heel is raised, thereby closing

the hi-hat cymbals with a tight 'chick' sound. On count 'three'

the heel comes down on the heel-plate and the ball of the foot is raised.

On count 'four' the ball of the foot comes down, closing the cymbals

as the heel is raised. (See Example 2) This technique produces

a nice, steady, quarter-note pulse in the hi-hat foot: heel, toe, heel,

toe, etc. It's important to remember that the heel always comes down

on counts 'one' and 'three'. The ball of the foot comes

down on counts 'two' and 'four'. The hi-hat should produce

a tight 'chick' sound when closed on counts 'two' and 'four'.

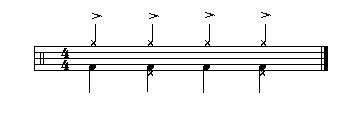

Ex. 2

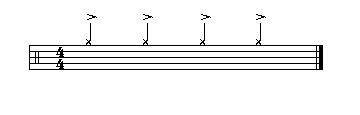

The bass drum

In much of modern jazz drumming the

bass drum takes on the role of a third-hand. That is, its role

becomes more like that of the snare drum as it interjects rhythmic ideas into

the overall mix. Nevertheless, it is still a good idea to develop the

ability to play four-on-the-floor. Four-on-the-floor simply

means playing straight quarter-notes on the bass drum. This was one of

the primary time keeping devices in the swing era. With the advent of be-bop

the bass drum took on a more 'soloistic' role and began to participate in the

rhythmic 'comping' previously reserved for the snare drum. Even

though the bass drum became less of a time keeper during the be-bop era, many

drummers still maintained the ability to play four-on-the-floor.

It's a useful technique and should not be neglected. The main point to

keep in mind when playing four-on-the-floor in a modern jazz context

is that it should be played very softly. This technique is sometimes referred

to as feathering the bass-drum. The beater will be released only

an inch or so from the head. A heel-down approach seems to work best for

this bass drum technique. Don't mash the beater into the head. Release

the beater and let the natural tone of the bass drum resonate. Keep the

volume of the bass drum very low. It should almost be felt rather than

heard. Example 3 shows the bass drum and hi-hat combined.

Ex. 3

You should be aware that many modern

players do not play straight quarter-notes on the bass drum. In these

exercises we are primarily using four-on-the-floor because of its value

as a foundational technique, although it can also be very practical. The

ability to lock down the time while adding an extra element of 'low-end' can

tie everything together, particularly when playing earlier styles of jazz.

Just be aware that despite its usefulness, four-on-the-floor may not

be applicable to every playing situation.

Combining hi-hat, bass drum

and ride

We will now combine the hi-hat, bass

drum and ride cymbal. Start by practicing the 'two' and 'four'

hi-hat with the four-on-the-floor bass drum. After this is comfortable

add straight quarter-notes on the ride cymbal. (See Example 4)

Return to your recordings and play along with some slow to medium tempo jazz

tunes. Keep the quarter-note pulse on the ride cymbal very even.

Focus on your sound

and the balance between the hi-hat, bass drum and ride cymbal. The ride

cymbal should predominate. The hi-hat adds weight to counts 'two'

and 'four'. The bass drum should be extremely soft.

Ex. 4

Practice this with various tunes

until it becomes comfortable. Try to project a feeling of swing

in your playing. Listen carefully to the rhythm section you are playing

with and copy their feeling while still maintaining a strong quarter-note pulse.

Once you are comfortable with this it will be time to move to the next section:

the skip note.

The skip note

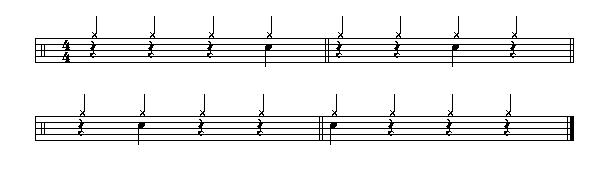

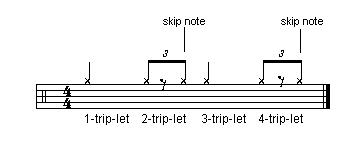

At this point we introduce the device

that gives the jazz cymbal rhythm its unique identity: the skip note.

The skip note is simply the third note of an eighth-note triplet. Typically

this occurs on the eighth-note triplets on counts 'two' and 'four'.

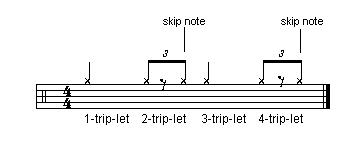

(See Example 5)

Ex. 5

When playing this pattern be sure

not to accent the skip note. The emphasis should be on the quarter-note

pulse. Strive for a smooth sound, where each note is connected to the

note that follows. Maintain the triplet subdivisions. Count out

loud, "1-trip-let, 2-trip-let, 3-trip-let, 4-trip-let", etc. Some people

use a mnemonic device such as saying, "dog.... walk-the-dog.... walk-the-dog",

etc., to get the feeling of the jazz cymbal rhythm.

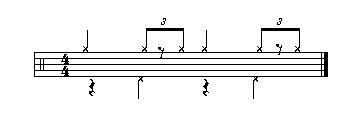

Next add the hi-hat to the cymbal rhythm. (See Example 6) Use the rocking technique on the hi-hat and make sure the cymbal and the hi-hat strike exactly together on counts 'two' and 'four'. There should be no flams between the hi-hat and cymbal.

Ex. 6

Once you are comfortable with the hi-hat and cymbal, add the bass drum on straight quarter-notes. (See Example 7) Play the bass drum very softly. The bass drum strikes exactly with the ride cymbal on counts 'one, two, three, four'. The bass drum, hi-hat, and ride cymbal strike together on counts 'two' and 'four'. You may want to record yourself playing this pattern to make sure there are no flam sounds.

Ex. 7

Practice this pattern along with

a variety of jazz recordings until it becomes comfortable. Balance the

sound between the bass drum, hi-hat, and ride cymbal. Above all, try to

make your playing swing. Spend a reasonable amount of time becoming comfortable

with this pattern. This will be the basis for the next section:

'Comping'.

Note: Before continuing with Part 2 of Jazz Drumming Jumpstart, make sure you are comfortable with the concepts and examples given in Part 1.

Part 2 - Comping

What is Comping?

Comping is short for "accompanying".

Comping is how the rhythm section instruments, such as piano, guitar, and drums

support the soloist. Comping provides rhythmic variety and impetus for

the soloist. The drummer's job is to support the soloist. As a drummer

you should play a variety of rhythmic ideas which contribute to the flow of

the solo you are accompanying. Comping is a give-and-take between soloist

and accompanist (i.e. drummer). Sometimes the drummer will interject new

ideas to push the soloist. Other times he may lay-back and respond to

ideas played by the soloist. As a jazz drummer, comping will be your main

improvisational activity. You will spend a great deal more time accompanying

other soloists than you will playing solos yourself. For this reason,

it is critical that you understand the basics of comping.

Comping seems to be one of the primary

areas where novice jazz drummers encounter difficulty. Repetitive, plodding

and uninteresting comping is a dead give away of an inexperienced jazz drummer.

In the sections that follow, I'll try to explain the basics of comping on the

drumset, and also give some suggestions on how to make your comping sound like

that of an experienced jazz player.

Comping and coordination

The essential technique for effective

comping on the drumset is coordination. The drummer must develop the ability

to play rhythmic phrases in a coordinated manner. In its simplest form

this type of coordination will consist of a repetitive pattern played in one

or more limbs, while another limb improvises rhythmic ideas. The repetitive

part can be considered an ostinato. The Harvard Dictionary of music

defines an ostinato as, "a clearly defined phrase that is repeated

persistently, .... usually throughout a composition or section." In

traditional jazz drumming, this is often the role of the ride cymbal, hi-hat,

and possibly bass drum. Therefore, these comping examples will consist

of repetitive, or ostinato, patterns played in the ride cymbal, hi-hat

and bass drum, while the snare drum improvises. This is the most common type

of comping found in jazz drumming.

I like to think of comping as the practical application of jazz coordination. This is an important point to keep in mind. Many players spend thousands of hours developing complex coordinated patterns, but sometimes these patterns aren't particularly useful in real playing situations. In my opinion, the main purpose of jazz coordination is to play swinging time, while providing the soloist with interesting musical accompaniment. This does not have to be a difficult, complex, or esoteric process. The goal is to make music. Everything we practice and play should be directed toward that goal. This is an area where we can really jumpstart our playing by focusing on the essential ingredients used in effective jazz comping.

Developing basic comping

skills

So how do we go about developing

practical jazz coordination? We can start by analyzing the playing of

experienced jazz drummers and developing some general rules of thumb.

Despite the seeming complexity of jazz drumming, it's been my observation that

a good deal of practical jazz coordination can be broken down into a few basic

patterns. We

will begin by looking at two of those patterns. The first pattern involves

playing the snare drum on quarter-note pulses. In other words, the snare

drum will be played on some combination of counts one, two, three,

or four. The second pattern involves playing the snare drum on

the third note of an eighth-note triplet. These notes can be felt as anticipations

to the main quarter note pulses. By developing these two simple ideas

we will start to build the foundation of our jazz comping vocabulary.

As you study these examples, keep in mind that you are learning the jazz language. The point is not to memorize a collection of licks or patterns. The point is to develop the coordination and musical skills that will allow you to create and communicate in the jazz style. In that regard, playing along, and listening to as many jazz recordings as possible is very important. Always try to apply what you learn to real playing situations. One of the best ways I know to learn jazz drums is to play along with recordings.

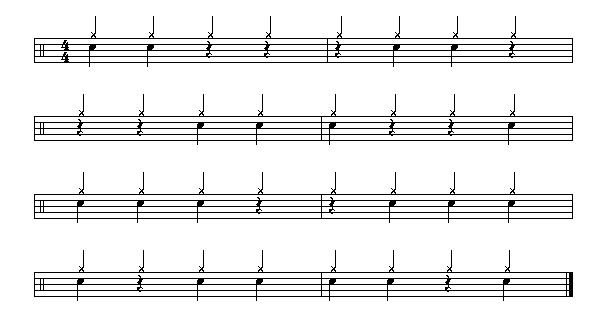

Comping using quarter-notes

Lets start with something very simple.

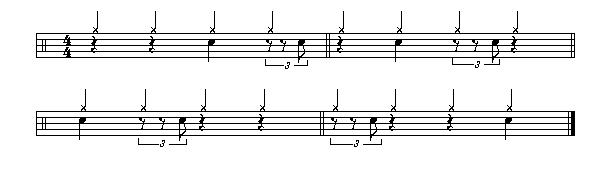

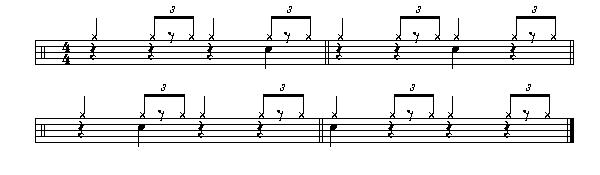

Practice the following quarter-note comping exercises. (See Example 1)

The ride cymbal plays straight quarter-notes*. The snare drum plays various

quarter-note patterns. Play 'two' and 'four' on the hi-hat.

The bass drum should play straight quarter-notes. Remember to play the bass

drum quietly. All unison notes are struck exactly together; no flams.

Practice each measure many times until it is completely comfortable.

(Note: To simplify the notation,

these remaining exercises do not have the hi-hat and bass drum notated.

You should continue to play the hi-hat on 'two' and 'four' with

the bass drum playing straight quarter-notes. Later, you may omit the

bass drum if you prefer.)

Ex. 1 (Remember

to play the hi-hat on 2 and 4.)

* These initial comping exercises use straight quarter-notes on the ride cymbal. This will allow you to concentrate on the comping figures played in the snare drum.

Practice suggestion for the remaining examples.

Ex. 2 (Play

the hi-hat on 2 and 4.)

After you become comfortable with these patterns practice them with some jazz recordings. When playing with the recordings vary the patterns and mix them up. Strive for variety in your comping. In some measures don't play the snare drum at all. In other measures play different combinations of snare drum quarter-notes. Concentrate on the sound and balance between the various voices of the drumset, and as always, try to swing.

Adding triplets

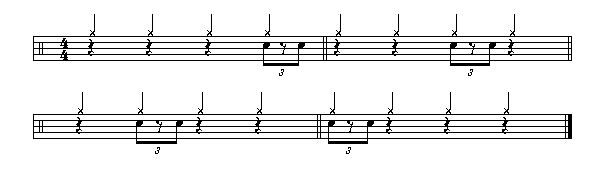

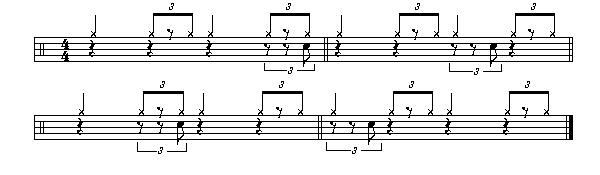

Now let's try some patterns with

the snare drum playing the third note of an eighth-note triplet. This

type of pattern is extremely common and very useful. An easy way to think

of this pattern is that the snare drum is slightly anticipating the cymbal notes.

You don't need to get caught up in the math of the eighth-note triplets.

Just feel the snare drum notes as anticipations to the cymbal notes. You will

hear patterns like these played by almost every jazz drummer.

Ex. 3 (Play

the hi-hat on 2 and 4.)

Tip: Snare drum

patterns like those above are some of the most useful comping figures you

will learn. Make sure you master the ability to play the third note

of any triplet in the measure.

As usual, practice these patterns with as many recordings as possible. Vary your comping patterns and make it swing.

Combining quarter-notes

and triplets

Now we will begin combining the two

ideas. Example 4 combines the snare drum played on quarter-note

pulses with the snare played on the third note of eighth-note triplets.

Think of the quarter-notes as being played in unison with the ride cymbal.

The third note of the eighth-note triplets anticipate the ride cymbal notes.

Practice each measure separately until it is comfortable, then mix the measures

up and combine them with other patterns.

Ex. 4 (Play

the hi-hat on 2 and 4.)

Example 5 consists of snare drum notes on the first and last note of an eighth-note triplet. (The middle note of the eighth-note triplet is omitted.) Be sure to close the hi-hat cleanly on counts 'two' and 'four'; no flams between the hi-hat, cymbal and snare. Practice each measure many times, then practice them with some recordings.

Ex. 5

(Play the hi-hat on 2 and 4.)

Example 6 consists of more patterns utilizing only the third note of eighth-note triplets. As mentioned earlier, this is a very useful figure. Make sure you can play the third note of any triplet in the measure.

Ex. 6 (Play

the hi-hat on 2 and 4.)

Practice all of the preceding exercises with as many recordings as possible. Keep a steady quarter-note pulse on the ride cymbal and keep it swinging. Remember that all of the above comping figures are based on only two rhythms: 1) straight quarter-notes 2) the third note of an eighth-note triplet. That's pretty simple stuff.

Incorporating the 'Skip'

note

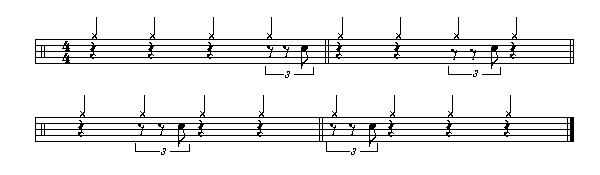

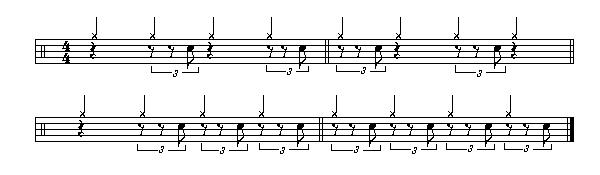

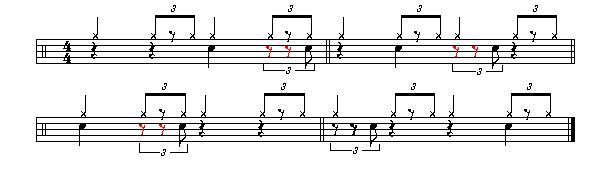

So far we have developed some basic

jazz coordination while playing straight quarter-notes on the ride cymbal.

The next step is to incorporate the 'jazz cymbal rhythm'. This simply

means adding the 'skip' note to counts 'two' and 'four'.

You will recall from Part 1 of this article that the jazz cymbal rhythm is played

like this:

Practice the previous examples again, but this time using the jazz cymbal rhythm instead of straight quarter-notes. The hi-hat will continue to play on counts 'two' and 'four'. You may also play feathered quarter-notes on the bass drum. Practice each measure separately repeating it until it is comfortable. As you become familiar with the various examples mix them up and combine them in different ways. Variety is important in your comping. Don't be afraid to leave space. You don't have to play a comping figure in every measure. Strive for a smooth and legato sound from the cymbal and make the patterns swing. Practice all of these patterns by playing along with recordings.

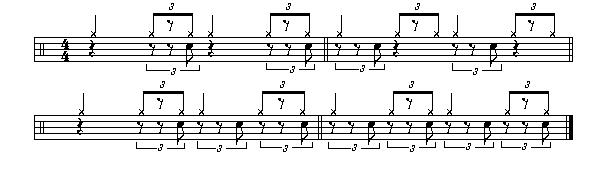

Ex. 7 (Remember

to play the hi-hat on 2 and 4.)

Tip: You should practice the jazz cymbal pattern to the point where it becomes automatic. Once you can put the cymbal rhythm on 'auto-pilot' it will become much easier to feel and play the comping figures below. Remember that the third note of an eighth-note tiplet is felt like an anticipation to the main cymbal notes on counts 'one, two, three, four'.

Ex. 8 (Play

the hi-hat on 2 and 4.)

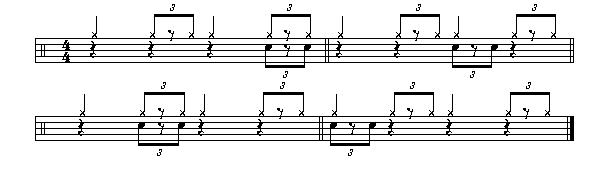

Ex. 9 (Play

the hi-hat on 2 and 4.)

Ex. 10 (Play the hi-hat on 2 and 4.)

Ex. 11 (Play

the hi-hat on 2 and 4.)

Here's an MP3 of Examples 7 through 11 played at a medium-slow tempo. Each measure is played twice. The examples are played one after the other in succession. This MP3 is only intended to quickly demonstrate what the examples sound like. This is not how they would normally be played or practiced. Refer to the suggestions following Example 1 for tips on how to practice and utilize the examples.

By this point you should be well on your way to developing a good basic vocabulary in jazz coordination and comping skills. Here are a few more suggestions to help your playing.

Good luck and have fun!

In Part 3 of this article we'll look at a few more comping figures and some other musical devices commonly used by jazz drummers. See you next time!

Discography

Here are a few suggested recordings

for 'play-along' practice.

These are just a few suggestions. There are hundreds of good recordings from the 50's and 60's. Many were recorded on the Blue Note, Atlantic, and Impulse record labels. It won't be difficult to find a vast assortment of great practice material. Look for recordings featuring drummers such as Max Roach, Art Blakey, Roy Haynes, Jimmy Cobb, Shelly Manne, Billy Higgins, Art Taylor, Louis Hayes, Frankie Dunlop and Mel Lewis.

Any comments or suggestions about

this article may be directed to:

kbarrett@funkdrums.com