While visiting various drumset forums I have noticed that many questions will crop up

repeatedly. In this FAQ section I have attempted to collect some answers to a few of these

questions. I hope that by organizing these questions and answers into a FAQ document I can

create more informative and thoughtful answers. The responses found here are certainly not

definitive. They are just my thoughts on some commonly asked questions.

Contents

How do I improve my double stroke roll?

The double stroke is an extremely important and useful part of any drummer's vocabulary.

The ability to execute clean doubles can greatly enhance your playing. In order to make

doubles sound as clean and even as possible, it is necessary that each stroke be played

with the same amount of force or power. In other words, the main stroke and the subsequent

rebound should be of the same volume. In reality this will be impossible to completely

achieve. The second stroke of a double is a bounce, and by it's nature will be somewhat

softer than the initial stroke. This tendency can be largely overcome by focusing on the

second stroke of each double. By practicing doubles with an accent on the second stroke we

can develop control of the rebound and to a large extent make our double stroke rolls

sound (almost) perfect.

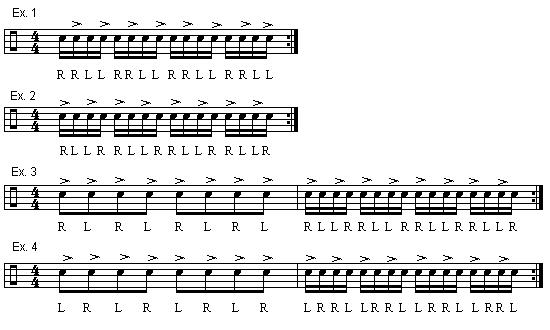

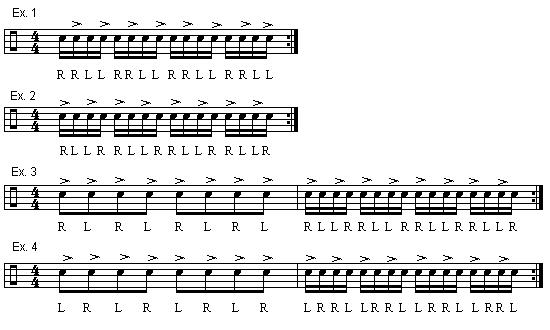

Here are a few examples.

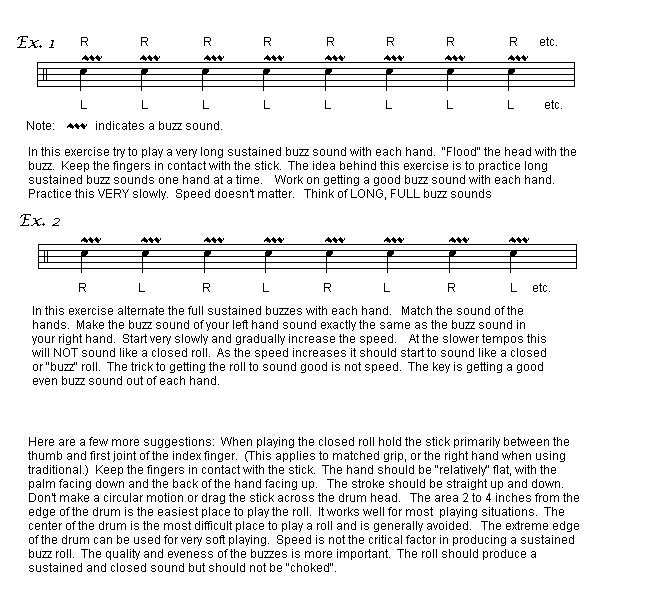

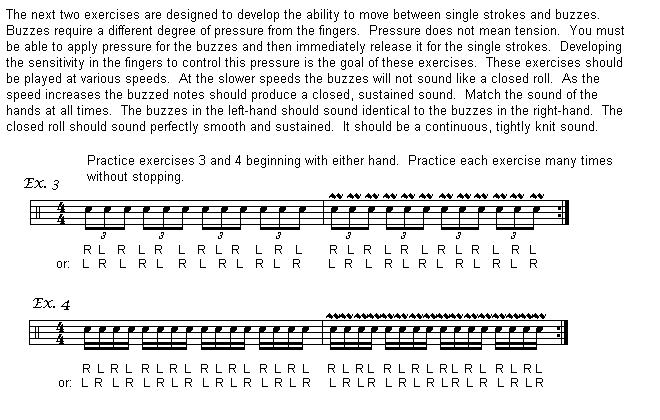

Ex. 1 shows the double stroke roll with the accent on the second stroke. Ex. 2 shows

another sticking for the same exercise. By beginning the exercise with a single stroke we

displace the accents and make the exercise a little bit easier to feel. The accents now

fall on a strong pulse. Ex. 3 shows a combination of single strokes and doubles. Once

again the second stroke of each double is accented. Ex. 4 is the same exercise but

starting with the left hand.

These are just a few exercises to demonstrate the concept. For a more in depth treatment

of rebound control see George Lawrence Stone's two books, Stick Control and Accents

and Rebounds.

Back to Contents

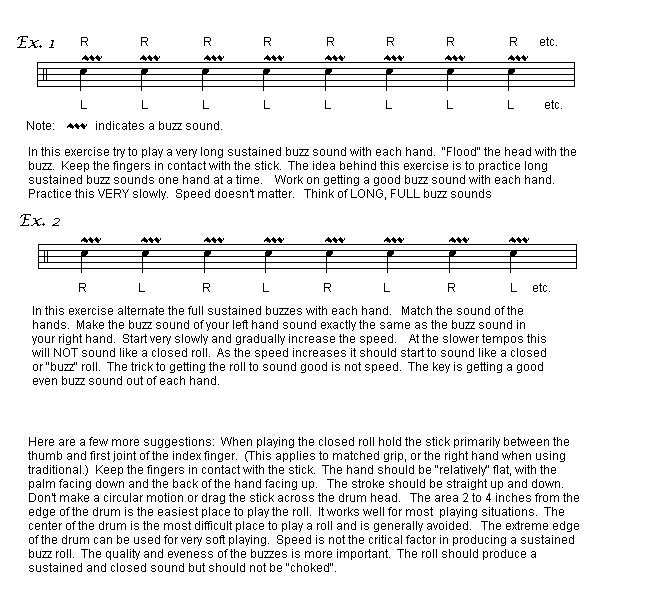

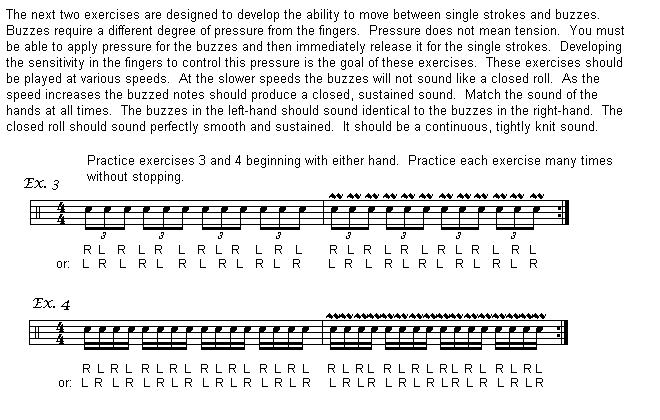

How do I improve my closed (buzz)roll?

The closed, or buzz roll, is one of the most important techniques a drummer

can master. It is also perhaps the most difficult. The sound of the buzz roll

should be perfectly smooth, with no breaks or uneveness whatsoever. It should

be one continuous sound. Since the buzz roll is the technique by which a drummer

creates a sustained sound it should mimic the long tones produced by wind and

string instruments. Unfortunately drummers don't have the advantage of

sustaining a sound with the breath or drawn bow, so they must emulate a

sustained sound by use of the buzz roll. The following exercises are meant to

aid in the development of a smooth buzz roll. When practicing them keep

in mind that the ultimate goal is to produce a completely smooth and unbroken

sound.

The following MP3 contains a quick run through of the exercises described above.

In actual practice you should take a much longer time to complete each exercise.

Buzz Roll MP3

Back to Contents

Bass Drum Technique

Should I play "into" the bass drum

head?

A drum will always sound its best when tuned to its most resonant pitch and allowed to

vibrate freely. One way to get a drum to resonate freely is to get the striker, be it

stick or bass drum beater, off the head. This goes for snares, toms, and bass drums. With

a bass drum this resonance can sometimes be a problem. In a small group setting it may

make the drum sound to boomy and overpowering. That's why drummers started using felt

strips on their bass drum heads. With the advent of rock a more articulate sound was

desired so people started using pillows, blankets, etc. The problem with heavy muffling is

that it diminishes the volume of the drum. Leaving the beater against the head is also a

form of muffling. It prevents the head from vibrating, therefore diminishing its volume.

If you want to get a big sound out of a drum reduce the muffling and get the beater off

the head. I believe a well tuned 20" bass drum played with good technique, will have

a bigger sound than a heavily muffled 22" or 24". The trick is to use the

minimum of amount of dampening to get the desired sound. Different styles of music require

different levels of dampening. Most of the dampening can be achieved by a pre-muffled head

and/or one of those bass drum pillows made by Evans and DW. For most purposes the

dampening should not come from digging the beater into the head. That may be OK for an

occasional accent, but it shouldn't be the basis of your technique. Its not the way to get

a good sound or use the physics of the instrument to help you play. You wouldn't play toms

and snare by leaving the stick on the head. It doesn't sound good. It is also inneficient.

The same thing goes for the bass drum. If you dig the beater into the head every time you

want to make a stoke you need to first release it (because it's resting on the head). That

means additional work and delay before you can play the next stroke. Get in the habit of

playing "off" the head and you should notice an improved sound and more fluid

technique.

How tight should the spring tension on my

bass drum pedal be?

The bass drum it just another drum. The same physics apply to it as any other percussion

instrument. An insteresting thing to try, which I first saw suggested by Ed Soph, is to

completely disengage the spring on your bass drum pedal. Then try to play single strokes.

You may discover some inefficencies in your bass drum technique. The beater should rebound

from the head just like it does on the snare and toms. Try to not let the spring

compensate for poor technique. The spring is really just an aid to the natural rebound of

the beater. If you're playing with a fluid stroke the spring should not need to be very

tight. Start with a loose spring tension and then only tighten it to the point where the

pedal will respond as quickly as your foot. The pedal tension and the speed of your foot

should be in sync. Going beyond that point is overkill and will make your playing tense

and cause quicker fatique. The name of the game in all musical performance is relaxation.

Use common sense and examine the physics of what you are attempting to do.

Should I play the bass drum heel up or heel

down?

In one sense heel up is similar to using finger control. It's an aid to playing fast

groups of notes and therefore is a very useful technique to develop. When playing longer

groups of fast notes lifting the heel "slightly" (i.e. 1/4 to 1/2 inch) will

help keep the lower leg muscles relaxed. Also finding the "sweet" spot on the

pedal is important. It's usually about 3 to 4 inches from the very top of the pedal. Use

the ball of the foot, not the toes. For slower patterns you can leave the heel down or up.

Just remember to release the beater from the head. If you are concerned about volume when

playing heel down I will mention that several prominent players recommend a heel down

approach. A few being John "JR" Robinson, Billy Cobham, and Mike Baird. I refer

to these guys because they all play in high volume situations and the heel down approach

works perfectly well for them. As an experiment try recording your bass drum sound playing

both heel up and heel down. Don't have the drum heavily muffled. Make sure to release the

beater and use a full stoke when you are playing heel down. You may be pleasantly

surprised at the amount of volume you can produce with a heel down technique. One other

thing worth mentioning is throne position. Try moving your throne back a bit and sitting

toward the front edge of the throne. By moving the throne back your ankle should be in a

more relaxed postition than if you are are sitting very close to the bass drum.

Back to Contents

How should I count odd time signatures?

Odd time is generally considered time signatures other than the usual 4 beats, 3 beats, or

2 beats to a measure. In other words 4/4, 3/4, and 2/4 would NOT be considered odd time.

Time signatures with 5 beats, 7 beats, 11 beats, etc. to a measure ARE considered odd

time. This may serve as a general rule of thumb. Most Western music (i.e. music coming

from the European tradition) is played with 4, 3, or 2 beats (or counts) to a measure.

Anything else is unusual, or ODD. That's a simple definition of odd time.

As far as counting is concerned, odd time signatures can almost always be broken down

into smaller groupings of notes (usually groups of two's and three's). For example, 5/4 is

commonly felt and counted as a group of 3 quarter notes followed by a group of 2 quarter

notes. So you might count 123,12 123,12 etc.. It could also be reversed and counted

as 12,123 12,123 etc. It doesn't matter if it's written in 5/4, 5/8, or 5/16, the

principle is the same: feel and count the rhythm in groups of two's and three's. The

phrasing of the particular song will dictate whether you feel and count 12,123 or

123,12. A famous example of odd time is the tune Take Five, recorded by the Dave

Brubeck Quartet. It is played as 123,12. Listen to the tune and you can hear the

groupings of 3's and 2's. The same principle can be applied to other odd time signatures.

For example 7/8 might be counted as 123,12,12 or 12,12,123 or even 12,123,12.

11/16 might be counted as 12,12,123,12,12 or maybe as 123,123,123,12. The

important thing to remember is that the phrasing of the song dicatates how the groupings

of two's and three's are felt.

Some good listening for odd time signatures are recordings by the Don Ellis big band,

some Dave Brubeck recordings, the Mahavishnu Orchestra, and Frank Zappa. A good book is

Ralph Humphrey's text entitled Even in the Odds.

Back to Contents

Back to the main

page